Adoptability Assessment

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Review functionality, technical quality, and availability of support as well as the project's sustainability and responsiveness to its user base when evaluating an open-source product for adoption.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: To understand if a project is likely to develop a secure-as-possible product, look for: a documented process for reporting security vulnerabilities; security patch releases; updated third-party dependencies; and for more mature projects, possibly a Common Vulnerability Exposure number(s) (CVE) and a published security audit.

EXAMPLE: The financial inclusion DPG Mifos has a CVE related to the Mifos-Mobile Android Application for MifosX. The problem has been fixed, but the public documentation is a sign of a mature project that takes security seriously and is willing to enlist the support of global security researchers and developers to build a better product. The DHIS2 DPG also publishes CVEs, along with a clear process for reporting vulnerabilities.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: If possible, work with vendors that can show solid, public evidence of their contributions to the project. The existence of multiple, diverse vendors providing commercial support is practically a guarantee that the product is as stable and reliable as possible, while looking through public reviews and the bug report database will give you additional insight into a product's stability and reliability.

EXAMPLE: The digital ID DPG MOSIP supports a thriving community of several dozen commercial partners, such as systems integrators and biometric solution providers.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Thorough product installation and initial configuration documentation indicates a product that's actually meant to be used. Also ensure that documented Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are available. These are necessary to the full range of the programmatic functionality you'll probably need, especially if you will work with data at scale (although a lack of published APIs isn't uncommon for early stage open-source products, but if this is the case, they should be on the project's roadmap). Lastly, be sure to get a detailed understanding the product's ability to import/export data, as you will surely need to work with legacy data at some point. Data portability also enables you to switch systems or vendors, should the need arise.

EXAMPLE: The health information management system DPG DHIS2 publishes clear documentation about installation and configuration as well as its Web API, which enables external systems (e.g. third-party software, web portals, and other internal DHIS2 modules) to securely access and manipulate DHIS2 data. The DPG MOSIP also publishes good documentation on its APIs.

A lot of open-source products are available as commercial-off-the-shelf solutions; often they are fairly straightforward to integrate and do not require much customization.

This modules outlines general but essential points to consider in assessing such solutions for adoption suitability.

FUTURE WORK: What are software engineering best practices and deeper technology choice considerations for DPGs, such as how to build for scalability?

KEY RECOMMENDATION: To evaluate an open-source product for adoption, you need to look at it from several different perspectives:

Functionality. Whether it has the functionality you need, either right now or plausibly planned on a roadmap (a roadmap that you may, in some cases, decide to influence or help accelerate). Does it provide Application Programming Interfaces (APIs)? Robust data portability? Is it extensible?

Technical quality. This is just the technical quality of the implementation: how well did they do what they meant to do? Is the software stable and reliable? Will it scale to the number of users you need? Does the project follow good security practices?

Sustainability. The long-term sustainability of the project: is there just one lone developer working in her spare time, or, at the other extreme, are there multiple companies paying developers to collaborate on maintaining and extending the project? (See the Community module for more on this topic.)

Responsiveness. Historically, how responsive is the project to its users? Do bug reports get processed in a timely fashion? Are contributions welcomed? Is there a way to influence the roadmap? When security vulnerabilities arise, does the project handle them promptly and competently? Are there community participation guidelines?

Support. Is there up-to-date documentation? Are there active user forums? Are commercial support providers available for you to hire, and if so, are they constructively integrated into the project's development community?

The sections that follow elaborate on some of the areas above and form a kind of checklist that you can use in evaluating an open-source product for adoption as a DPG (or as part of a new DPG to be created).

Throughout this module we will sometimes use the word "product" and sometimes use the word "project". They are closely related but emphasize different things. The "product" is what you deploy and may also pay for: a packaged DPG, often accompanied by a support contract or at least by the potential availability of on-demand commercial support should you ever need it. The "project", on the other hand, is the living software community in which developers and organizations collaborate to produce the software that is the core of the product, along with documentation, support, and more (depending on the project type; see the Community module).

Typically, the organizations that provide product-shaped offerings are also deeply involved in the project. As you'll see below, that's one of the things to look for when evaluating both projects and vendors.

Assessing Security

There are no guarantees when it comes to computer and network security. Even the largest companies and the most careful, thorough government agencies still get hacked from time to time. Adding a new software system to your existing portfolio only increases risk -- to use the language of computer security, you've expanded your "attack surface".

However, at the point when you are still evaluating a product, there are some steps you can take to lower that risk. For the most part, those steps do not involve actually evaluating the code itself -- that would be a highly demanding technical task, and most procurement evaluation efforts do not have the capacity to undertake it. Instead, you look for certain external signs that indicate whether the project has its security house reasonably well in order. For the most part, these are evaluations of "project" more than of "product", but we will note where that distinction is important.

Does the project have a documented and secure way to receive external reports about security vulnerabilities?

If you are working with a vendor that has a relationship with the project, then that vendor will know the answer to this. The project should document a method by which anyone can report a security vulnerability in such a way that that report does not become public until after the vulnerability is fixed and a new release of the product has been made. (This means that such reports are not normal, publicly-posted bug tickets -- a rare exception to the rule that information in an open-source project is all publicly visible.)

A good example of a clearly documented security vulnerability reportin process is from the Fedora Project, whose Fedora Linux is part of the DPG Resources collection. The DHIS2 DPG also publishes a clear process for reporting security vulnerabilities.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Look at the project's web site or documentation to see what it says about reporting security vulnerabilities. If applicable, ask the vendor.

Does the project have a way to make security patch releases? And has it done so?

A security patch release is a new version of the product that differs from a previous version only by the inclusion of a security fix. If a project has a history of putting out such releases, that increases the likelihood that the project is handling security vulnerabilities competently in general.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Look at the project's release history and see if there are any security patch releases, which would indicate that the project is handling security vulnerabilities at least at a base level of competency.

Does the project acquire CVE numbers for security problems?

A "Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures" (CVE) number is a globally recognized unique identifier for a specific vulnerability in a specific piece of software.

A CVE number looks something like "CVE-2021-0160," where the first numeric part is the year, and the second is an increasing sequence number (it may exceed four digits if more than 10,000 numbers are handed out in a given year). The CVE list is maintained at cve.mitre.org. Its purpose is to a provide standardized name for every known computer security problem, so that everyone has a single, canonical name to use when discussing that problem and a central place to go to find out more information.

FURTHER READING: For a more detailed explanation of how CVE numbers are acquired, used, and evaluated, see Producing Open Source.

For a particularly clear exposition of how one large open-source project uses CVE numbers, see the Debian GNU/Linux project's description.

This may sound surprising, but if a project has a history of obtaining CVE numbers for vulnerabilities, for example as the DPG Apache Fineract does, that's actually a good sign: it means the project is integrated into the wider community of global computer security response and is following the standard procedures.

Note that a project having many CVE numbers associated with it does not necessarily signify inattention to security problems. Often it signifies the opposite: that the project takes security very seriously and therefore obtains CVE numbers even for small, trivial security problems that don't really put user data at risk.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Search the CVE list to see how well-represented the product you're considering is in the CVE database.

Mozilla's security web site is another example of how a commercial company that fosters numerous open-source projects communicates around security issues.

Are the project's dependencies up-to-date?

This does require some mild technical evaluation of the project itself, not of the raw source code but of the third-party dependencies the project relies on. If you have the technical capacity to browse the dependency (for the latest version of the project) and see how up-to-date those dependencies are, that can shed some light on how highly the project prioritizes security concerns.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Confirm that third-party dependencies are updated.

Has the project had a professional security audit performed?

It's not common for open-source projects to have professional security audits conducted, because such audits are expensive. However, it happens sometimes, and when it does happen that's a very good sign. The results of the audit, which review security issues at a particular point in time, should be publicly available from the project's home site (after any important issues found by the audit have been fixed and released, of course).

If you are seriously considering using a product for especially sensitive data, then you might commission a security audit if you have the resources to do so and offer to make the results available to the project. You would send those results in however the project requests; typically, that would just be via their normal security reporting channels.

If the product has been implemented broadly, you might find public audit documentation that's specific to individual implementations. These are likely to cover processes and policies, such as adherence to national regulation, as well as the software itself, but they're still useful resources. For example, the National Audit Office of Estonia recently audited X-Road and found that implementing agencies weren't adhering to some of the security policies we recommend in the Policy module.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: See if any security audits are publicly available.

Stability and Reliability

You can make a reasonably accurate estimate a product's stability and reliability by looking at three things:

1) "The word on the street" -- that is, look at what people who already use that product are saying about it on the Internet.

2) The software's own bug report database.

3) The existence of vendors who offer commercial support for the software.

Taking them in order:

Regarding (1): Software fortunately does not suffer very much from the "fake reviews" problem found on non-technical retail/consumer review sites (e.g., Yelp, Amazon, etc). Most of what you see will honestly reflect people's actual experience. Therefore, your job is just to find the places where people whose needs and capabilities are similar to yours are posting their comments. Standard web search engines will get you pretty far and may be all you need. You can also search directly in sites that focus on the system administrator audience. The best known of these is probably Server Fault.

Regarding (2): If someone with even a little bit of technical knowledge spends about half an hour wandering through a project's bug report database, they can very quickly get an idea of whether the project suffers from stability and reliability problem. Sort by date and focus on recent reports (e.g., from within the last one or two release cycles). It doesn't matter if the project formerly had stability issues, as long as they're fixed now, and anyway many projects have such issues when they were first getting started. (Remember that the number of tickets present in a project's bug tracker is proportional to the number of users the project has, not to the number of actual defects in the software.)

Regarding (3): The existence of commercial support offerings is a very good sign -- in general, really, but especially for the stability and reliability of the project. Commercial support vendors have a very strong interest in the software's stability: unstable software costs them money because it requires their staff to do more interrupt-driven work.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: The existence of multiple, diverse vendors providing commercial support is practically a guarantee that the product is as stable and reliable as possible, while looking through public reviews and the bug report database will give you additional insight into a product's stability and reliability.

Scalability and Deployment Investment

An important part of evaluating a DPG is to evaluate the investment your team must make to deploy the DPG in a way that meets your requirements.

RECOMMENDATION: As a general rule, the more scalability you need, the more up-front investment you must make in configuring your deployment.

For example, many systems typically come with a default ("out-of-the-box") configuration in which all parts of the system are installed on one server machine, because that way is simplest to maintain. But if your intended usage needs to scale to millions of users (or to 1.25 billion citizens, as is the case with India's open-source digital ID solution), or to millions of some other kind of data item, then you will likely need a more complex configuration, with the database portion of the software running on many separate servers, various kinds of monitoring and automated health checks in place, etc. Such configurations are often documented and well-supported by the project too, they just aren't what the project offers as the default option, because many deployers don't need that kind of scale, and of course the project wants the majority of deployers to have the easiest possible out-of-the-box experience.

Thus, start by understanding your own parameters: how much investment, in terms of time and money, are you willing to make to support a given scale of usage?

If you are working with a vendor, they can help guide you through those calculations. If you are not working with a vendor, the project's designated user support forums are often a very good place to get rough estimates of the scale/investment ratio from people who already have experience deploying it. Make good use of those forums: search the archives for others who have asked scalability and deployment questions, and if you don't see the answers you need, then post questions yourself. That's what the forums are there for, and when you post a well-thought-out question you are actually doing the project a favor: if someone answers it, your question and their answer will be in the public archives for others to find in future searches.

Data Portability (Import/Export and Interoperability)

Data portability is the ability to import data into and export data out of a system, ideally to/from standard formats that are supported by other commonly-used software systems.

Sadly, data portability -- especially export capability -- is often under-evaluated or even largely omitted from evaluations. This may be because it is hard to imagine, when you are considering moving to a new system, that one day in the future you may be moving away from it. But for DPGs in particular, data portability is one of the most important concerns. There is often some legacy data, somewhere, that you will want to import into the system, even if you don't know at the time of the evaluation and procurement that that legacy data exists. And there are many reasons why you might be interested in exporting data even if you are not migrating away from the system to something else (see the below section Programmatic Control for more about these). Moreover, open projects must ensure they support extraction or importation of non-PII data in a non-proprietary format in order to qualify as a formal DPG (which circles back to the importance of open standards, another essential part to the definition of a DPG).

Data portability is one area where vendors sometimes give unreliable information or at least may quietly leave out certain exceptions and caveats. If you ask a vendor questions about import/export capabilities, be sure to make those questions as specific and precise as possible. For example, don't simply ask "Can the system export its data?" The answer will almost always be "Yes!" Instead, ask something like "Can the system export all of its data in standard format FOO such that it can be imported by Some Competing Program without any information being lost or miscategorized?", where "FOO" is the name of some actual format, and you've identified the particular competing program. Then you'll likely get a more nuanced and complicated answer, because import and export functionality tend not to be a binary, yes-or-no propositions. More often, there is an import/export feature but the real question is how much pre- or post-action data manipulation is required to get the end result that you need.

Even if you have vendor support, you should also search the Internet and the project's forums for reports from others about importing and exporting the data formats that matter for you.

Data Portability and Avoiding Vendor Lock-In

Remember that import/export functionality can be important to your ability to switch vendors, not just to switch systems. If you want to continue using the same DPG but change your support contract from one vendor to another, it is not always the case that the two vendors will be able to perform a smooth hand-off. Instead, the new vendor will often want to deploy their own copy of the system, using a deployment configuration that they are accustomed to, and move your data from the old system to the new system. In order to better enforce this point about data portability, agencies could consider adding a contractual clause that a vendor is required to put in additional hours above a certain baseline to port data to a new vendor implementation, should the need to switch vendor support arise at some future point.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Be sure to get a detailed understanding the product's ability to import/export data. Even if you have a vendor supporting you, search the Internet and the project's forums for reports from others about importing and exporting the data formats that matter to you. This will help you plan for needed resources and project scheduling as well as be better prepared should you need to switch vendor support at some point.

Programmatic Control (APIs)

Interacting with a system programmatically means other programs issuing commands to the system and being able to read/send data from/to it.

It is unfortunate that such a key concept is hidden behind the technical acronym 'API.' If you aren't already familiar with what APIs do, please take a moment to read the "Introduction to APIs for Non-Technical Readers" section in the Appendix: APIs as well as the example of Open Referral in the Appendix: Examples, then come back here.

Having a documented API as part of a service is very important. APIs make many things possible. The read-only side of an API enables sophisticated analytics, reports, and notifications, for example. The read-write side opens up the possibility of interacting with the system's data in ways beyond what the regular user interface allows. If the data in the system matters at all, eventually someone will want to work with that data in a programmatic way, and the only way to do that effectively at scale -- meaning scale for volume or for application to new areas -- is through an API.

APIs from Fineract and Mifos X enabled those financial inclusion DPGs to scale to support numerous use cases -- from traditional banks to digital-first neo banks and wallet/payment providers -- from over 400 institutions in 40 countries. In another example, the non-profit Population Services International (PSI) learned that many health ministries and other non-profits were using the DPG DHIS2 with Microsoft PowerBI for data visualizations, but the process for moving data from DHIS2 into the popular PowerBI product was cumbersome. DHIS2's well documented API enabled PSI to partner with BAO Systems to create programmatic connectivity to Microsoft PowerBI. The DPG Avyantra uses machine learning to improve diagnoses of infants affected by neonatal sepsis. Their application's modular approach and use of [APIs make it more easily extendable to diagnosing other critical medical conditions in neonates, infants, and children. Similarly, API availability for the DPG DHIS2 is helping its expansion into new sectors like education and logistics.

In some cases, the API could be as simple as an "export" button, causing a spreadsheet to be downloaded (usually in CSV -- "comma-separated value" -- format, a kind of baseline import/export format supported by all spreadsheet programs). But often a more sophisticated API would be better. For example, there may be queries or interrelations that are specific to the particular kind of data in question, and those queries might not be provided by most spreadsheet programs. A tailored API that is aware of such specificities can provide query functionality to support them. Also, sometimes there's just a lot of data, so much that it would be too slow to download it all in a CSV file. An API allows people to target the exact subset of the data they need and download only that.

Fortunately, when systems have an API, it is usually prominently documented and mentioned in the product's feature list. Check that documentation and search for examples on the Internet of people using that API to accomplish real-world tasks.

Even when a system does not have a published API, it's often the case that there is already an internal, unofficial API and the project is simply waiting until it settles down a bit before publishing it. The project roadmap or user forums may say more about this; also, as usual, an experienced vendor can point you to more information.

If a product works with data at any scale but has no API and no intention of developing an API, that is usually a bad sign. Unless there is some reasonable explanation for the omission, the lack of an API should be considered a serious point against enterprise-wide adoption of the system.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Ensure the availability of documented Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), which are very important to supporting a full range of the functionality you'll likely need. Check documentation and search for examples on the Internet of people using that API to accomplish real-world tasks. Lack of published APIs isn't uncommon for early stage open-source products, but this situation (or lack of a roadmap) is unacceptable for products intended to work with data at scale.

Extensibility

Software system extensibility can come under many different names: "plugins", "add-ons", "add-ins", and "extensions" or "extension modules" are the most common, though sometimes "components" is (confusingly) used too.

All of these things refer to the same basic idea: the ability to extend the system's functionality by adding new code from the outside in certain well-defined ways (see the Programmatic Control section above). Sometimes a system is even extensible in more than one programming language, though often there is a primary supported language that most users prefer and that is supported best. A system based on a modular architecture, with loosely coupled software components, is one that's more easily extensible.

Some well-known and widely-used open-source systems owe much of their success and growth to being easily extensible in this fashion, such as: WordPress, Drupal, Django, MediaWiki, Firefox, and Chromium. Extensibility has a long history and is not confined to open-source software, however. AutoCAD, a system for computer-aided drafting, has had an extension language since the mid-1980s, and Microsoft's Visual Studio development environment has a rich extension community primarily writing extensions in the Visual Basic programming language.

Extensibility tends to be a sign of maturity. Products usually become extensible after acquiring an initial user base and in response to the varied demands of that user base. Instead of incorporating every user request as a core feature (which would lead to a disorganized and unmaintainable core), the project keeps the baseline system relatively simple, and instead encourages a parallel community of extensions to be developed on top of that baseline -- often developed by users or by organizations supporting groups of users.

When evaluating a system, discovering that it is extensible at all is already a positive sign. The next thing to look at is the richness of that extensibility. How powerful is the extension language, how many extensions already exist, and how useful are they?

One quick way to answer these questions is to look for a listing of extensions. For example, WordPress has the WordPress Plugins marketplace, Firefox has Firefox Add-ons, etc. Look in the listing for a diversity of third parties offering extensions, especially for commercial vendors involved in that ecosystem.

The most promising sign of all is when you see multiple different extensions being offered that all do roughly the same thing. That signifies a truly active and competitive extension community, which in turn implies good things about the software system on which the extensions are based.

When you are evaluating vendors for an extensible system, you should prefer vendors that have demonstrated experience writing extensions, especially vendors who are well-represented in the public marketplace of extensions that may be used with the system (if any exist).

RECOMMENDATION: An open-source product's extensibility is often a sign of maturity, as it's developed enough to have a stable foundation and pushes flexibility through extensions that can change more often to meet more specific, and varied, user needs. When you are evaluating vendors for an extensible system, look for vendors that have demonstrated experience writing extensions.

(As a side note, the peak of extensibility is when extensions are where most new functionality is created. Veteran software architect Jim Blandy writes, in the book "Beautiful Architecture" (O'Reilly Media, 2009), that "[there is a] question we can ask of any extension language we encounter: is the extension language the preferred way to implement most new features for the application?" When an application "places its extension language at the heart of its architecture, [that is] a strong argument that the language's relationship with the application has been designed properly.")

Documentation

Most open-source software systems come with at least some documentation -- that is, documentation that is officially maintained by the project itself and published together with the software. Such documentation is actually a DPG requirement; see the DPG MOSIP for a good example of such documentation. In many cases, there is also a wealth of scattered and heterogeneous third-party documentation: "HOWTO" blog posts, answers posted on sites like Stack Overflow, etc.

The best way to evaluate all this documentation is through a limited set of shallow, task-oriented queries. Reading it all would be too time-consuming and pointless, because much of the documentation may be about features you will never use. Instead, pick a few questions that you can guess are likely to come up and see how quickly you can find areas of documentation -- in both the official documentation and in unofficial sources -- that address those questions.

There is one particular task-oriented inquiry that you should almost always make: look at the documentation for the system's installation and initial configuration. Whatever else you may or may not do with the system, the first step is always that you (or your supporting vendor) are going to deploy it. The project knows that's true for everyone, so if there's one part of the documentation that should be in at least decent shape, it's that. If the deployment documentation is missing or is obviously incomplete, that is a warning sign about the entire product.

When working with vendors, beware of those who try to steer you to their proprietary documentation for functionality that is part of the public product. Responsible vendors who are maintaining a healthy relationship with the project's development community will generally focus on improving the project's documentation rather than maintaining a separate, non-open-source set of documentation that's just for their customers.

KEY RECOMMENDATION: Look at the product's installation and initial configuration documentation. If this deployment documentation is missing or is obviously incomplete, that is a warning sign about the entire product. When working with vendors, beware of those who try to steer you to their proprietary documentation for functionality that is part of the public product.

Commercial Support Availability

The existence of commercial support offerings for a system, ideally from multiple vendors, is something to look for in an evaluation. The presence of commercial support means that someone else -- that vendor -- has already done an evaluation of the system and found it sufficiently useful and stable to invest money in training staff and creating a support offering.

Assuming you find vendors, then, how should you evaluate them?

One key thing to look for is the vendor's presence in the project's development and support communities. Does the vendor have staff taking active part in the development of the software? Does the vendor have staff both filing and responding to bug reports? Are they active in the discussion forums, both development-oriented and user-oriented?

You don't need to do the detective work from scratch. You can save yourself a lot of time by asking the vendor about their role in the project community, specifically asking them for evidence (e.g., the names of the staff and where to look for them). Then you can easily spot-check the claims yourself by searching in the project's public resources, primarily the code repository, the bug tracker, and the discussion/support forums.

If the project has a vendor listing page (see, for example, the DPG Mojaloop's business directory), the vendor should be on that list.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS: If possible, work with vendors that can show solid, public evidence of their contributions to the project. Again, it's a good sign if an open-source product has commercial support around it, such as consulting and development companies.

Non-Commercial Support Availability

Open-source projects often have quite responsive user support forums -- places where anyone who has deployed or who uses the software can ask a question and get answers from experienced users (for example, see the Apache HTTP Server user forum). The people who are subscribed to these forums are there for a variety of reasons. Sometimes they are there because they make heavy use of the software and want to gain as much information as they can from other users (but therefore are also available to respond to questions from newcomers). Sometimes they are there because they represent a vendor, either overtly or discreetly, and are helping to maintain the vendor's presence in the community. In general, as long as your postings adhere to the forum's stated guidelines, they will be welcomed. If you ask a question and no one knows the answer, you may get silence in response, but even then posting is usually still worthwhile in the long run: a response may come much later from someone who is deploying the software in a setup similar to yours, and once you have found each other via the forum, you'll be able to provide mutual support from then on (hopefully still using the public forum!).

The quality of non-commercial support can vary over time. Some projects have a healthy, enduring culture and process to consistently maintain support. Other projects overly depend on one or several individuals who take support upon themselves. In assessing a project's ability to provide open-source support, it can be useful to see who and how many people are providing that support over what time period. The strongest signal of high-level support will be when help is provided in general by a community and there is a culture of reinforcing that community activity. At the other end of the spectrum, one will find a project's lead developer heroically also playing the support role. That can work, but is sometimes an indication that the project overly depends on one person who might move on or burn out.

RECOMMENDATION: User support forums are useful resources in your evaluation (just as open user support forums will be important to others evaluating your DPG). Don't hesitate to ask questions.

Influence and Participation

Procuring a DPG is very different from buying a physical good like a truck or a desk. You do not, realistically, have much opportunity to influence the truck manufacturer, nor collaborate with them to improve the trucks that will be coming to the market next year. But with DPGs, that possibility very much exists, and this should be taken into account when evaluating both a particular DPG and your own current capacity for taking advantage of that opportunity (for more on the latter point, see the note later in this chapter about possible future work on assessing internal capacity).

The evaluative question being asked here is: "What routes does the project have for us to convert our own usage, and potentially some financial support, into useful inputs for the sustainability and direction of the project, thus gaining increased return on our own investment in choosing the product in the first place?"

When you are first evaluating a DPG for initial deployment, this kind of long-term investment analysis is usually premature. It is more appropriate to undertake it after you have already been using the DPG for some period of time and have some confidence that deeper investment is likely to pay off for your organization.

Most often, routes for influence go through vendors. Commercial vendors are often the organizations that have the greatest motivation to maintain a long-term contributor relationship with the project and the experience in the project's technical culture to know what goals can be accomplished in what periods of time. This is why evaluating the vendor's relationship with the project (as discussed above in Commercial Support Availability as well as in the Community module) is so important: the vendor can influence the project on your behalf.

It's also important to evaluate the project to make sure it has routes of influence available. You can do this indirectly, by asking your vendor(s) to show where their past attempts to influence have been successful and how. You can also do it directly, with a little more effort, by looking at the project's governance and the discussions that lead to new features and roadmap decisions. Although any form of open-source project governance can, in principle, be amenable to influence, in practice projects that are run by committee are more reliably amenable to influence, because you have the possibility of being on that committee -- or, rather, of being represented on the committee by an existing member. Recall too that open-source projects later in their lifecycle are often less open to influence, as they will generally prioritize stability. This is usually true for modular projects as well, although their exensibility does give you a path for influence (see the Community module).

Project governance documents are useful insofar as they describe the formal structure of how decisions are made. However, the way decisions are made in practice can sometimes diverge from this official method: as long as everyone in the project is happy, there is no reason for anyone to cite the rule book -- thus gradual drift from the rules can happen. As a newcomer evaluating the project, therefore, if you look only at the rule book you will only get part of the picture. You have to also look at some of the conversations in the development forums and see how decisions are made in practice. This knowledge, combined with input from your technical staff (if available) and vendors (if available) will allow you to make rough guesses about the possibility and usefulness of having long-term influence in the project and about what sort of commitment of resources that influence might require.

RECOMMENDATION: Open-source projects have lifecycles, and the maturity level of a project will generally dictate your ability to influence and level/type of investment needed.

If your own staff has the technical expertise to participate directly in the DPG's development community, that is an investment that may be worth considering. It usually starts with fixing bugs, first small ones and then larger ones, and eventually may progress to proposing and adding new features. The reason for this gradual progression is twofold: first, it takes time for the staff to learn the software's internals, of course. Second, it takes time for the staff to gain the credibility and standing in the project needed for successfully getting large feature improvements landed in the core code.

Because of the gradual nature of this progression, think carefully about your ability to make and hold to a long-term commitment as staff begin to deepen their investment. A few easy, small-scale bug fixes does not require great investment, but for staff to get much more involved than that will generally consistent managerial support. In some cases that may be a worthwhile investment, but in other cases it might not be the best use of staff time from your organization's perspective.

(Note that staff can always be encouraged to participate in user support forums, regardless of whether they are participating in any technical way. Presence in those forums is a good way to stay in touch with the project's currents and to develop expertise that can be very useful to have in-house, even if you also have a support vendor.)

FUTURE WORK: We were thinking of having a section "Internal Capacity Assessment" here. To produce it, one could start by collecting relevant points from all the other sections, then examine what specific internal capacities would be needed to take advantage of or implement the advice given in those points. It should be limited to outlining what's most important and what's most often overlooked in thinking about internal capacity, for DPGs specifically, and ideally come from talking through the toolkit with government agencies and others involved with DPGs; otherwise the topic could be too large and too general for this toolkit.

Ecosystem Mapping for Adoptability

The adoptability of a DPG depends on the the overall landscape of users, deployers, and technical investors in which that DPG is situated. In the sections above, we have discussed some elements of this landscape a bit already: sources of commercial and non-commercial support, the possibility of technical involvement from your in-house IT staff or from a vendor contracted for the purpose, etc. However, it's also useful to look at that landscape as a whole -- as an ecosystem of stakeholders and, where applicable, relationships between them.

When you're about to make an investment in a DPG, such as by deploying it for sustained use, it can be very helpful to take a step back and explicitly map out that ecosystem, in a quick, lightweight exercise. (This exercise is equally useful in planning to create a new DPG.)

Making such a map can reveal both gaps and opportunities. For example, an ecosystem map might reveal a gap by showing that the main sources of commercial support are effectively serving one large primary customer -- meaning that your needs might take second place to that customer's needs, so you might want to try to stimulate a new company to make its own support offering. Or an ecosystem map might reveal an opportunity by showing that there is another public agency already using the DPG and who that agency's sources of support are.

There are many ways to produce an ecosystem map, and you should not worry too much about procedure or completeness. It's better to do it quickly and easily, so that you don't delay the exercise. Take what's immediately visible to you in the DPG's discussion forums, bug tracker, and other easily accessible online sources. If you know someone who's involved in the project in some way, call them up and ask them some questions about who else is using the DPG, where sources of support are, and anything else they might know. You're looking for information about deployers, contributors, service and support providers, integrators, and competing or adjacent efforts.

Then draw a map of what you've found out, doing it as a group exercise if possible so that you draw on everyone's knowledge. The drawing should be messy and quick -- a year from now it will probably be out of date, and that's okay. Just hand-draw it on paper or on a whiteboard.

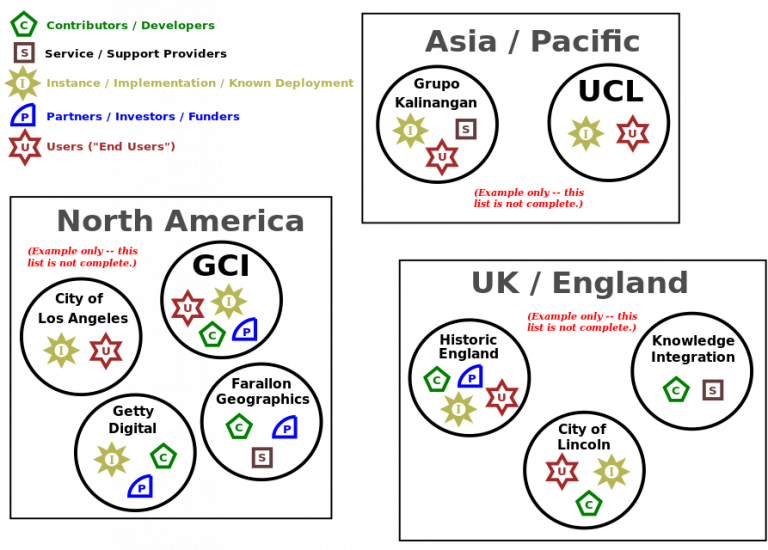

The figure below is a map drawn to identify stakeholders in the Arches Project. The original was hand-drawn, but we cleaned up a bit for publication.

Because we were interested in uncovering information about geographic distribution of support sources, this map includes regional groupings that might not be necessary on your map. Conversely, your map might show relationships (e.g., contractual relationships) between certain stakeholders that we did not bother to show here. This map did not focus on relationships because its purpose was to help us understand where the project was succeeding geographically and how to support participants spreading the project into new communities. But if you're drawing a map to help assess a DPG's adoptability, you should include the elements and relationships that matter most for your circumstances.

While there is no one right way to draw an ecosystem map, there are some pitfalls to watch out for -- signs that the map might be missing important information:

If the map looks like a star, with all the connections radiating out of one central entity, then the map is probably not capturing the true complexity and topology of relationships.

If it is more of a cloud than a map, then it might not be grouping entities in useful ways, e.g., it might be failing to separate them by the function they perform in the ecosystem

If the map tries to answer too many questions at once, it will be incomprehensible. It's better to focus on a few interrelated questions, such as who the deployers and support providers are and what the relationships are between them.

Once you have the map in front of you, factors relevant to adoptability that might not have been apparent before can suddenly become obvious. For example, you might notice that every other known deployer has deep in-house IT capability. If your organization does not have that kind of in-house IT capacity, that wouldn't necessarily mean that you shouldn't use the DPG, but it would at least indicate that a closer look at the deployment requirements may be in order.

Ecosystem mapping can reveal gaps in the landscape. For example, "rocket ship" projects often struggle to provide user support. If such support is important and the ecosystem does not provide it, you will have to find anther way to fill this gap.

RECOMMENDATION: A simple ecosystem map can help you think through other adoptability factors that might be relevant. What in the ecosystem actors, their types, and their distribution gives you additional insight? For the project's likely archetype, what would you expect to see in that ecosystem? Are there problematic gaps or useful opportunties?

Evaluation Checklist

This section summarizes the previous considerations around adoptability in a simple, unprioritized checklist.

Does the product meet your functional requirements?

- Do the functional Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) you’ll need exist, and are they well documented? Can you find examples of these APIs being used in ways similar to your plans?

- Will your data be portable?

- Can you extract or import non-PII data in a non-proprietary format? (a requirement of the DPG standard!)

- Can you import and export data in the formats you expect to need?

- Can you generally import and export data with an acceptable level of pre- and post- action cleaning and manipulation?

- Is the product extensible?

- Do many extensions exist, and are they being used?

- If you are evaluating a vendor to help you with an extensible product, does the vendor have a history of creating successful extensions for others?

Does the product meet your requirements for technical quality?

- Is the product as secure as possible?

- Is there a documented process for reporting security vulnerabilities?

- Are there published security patch releases? Is there a published process for publishing these patches?

- Are any third-party dependencies updated?

- Does the project publish Common Vulnerability Exposure (CVE) number(s)? (usually most relevant for more mature projects)

- Does the project publish security audits? (usually most relevant for more mature projects)

- Is the product stable and reliable?

- What’s your analysis based on bug reports?

- What's your analysis of public conversations around the product?

- Do commercial vendors offer services around the product?

- Is the product scalable enough?

- First, do you understand the scale you’ll require from the product?

- Does the default product configuration meet your needs?

- If not, is there an indication -- through formal documentation, product reviews, conversations in user forums, etc. -- that the product can scale to your needs?

- Can you invest appropriately to deploy and support the DPG to meet your scalability requirements?

- Again, do Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) exist and are they well documented? Can you find public examples of the product’s APIs being used for the level of scale you’ll need?

Does the project seem to be sustainable?

- Are there diverse, resource-committing participants?

- Based on a rough idea of the project's archetype, do you see the predicted types of participants?

- Are there commercial participants?

- What are the gaps and opportunities you see based on a project ecosystem map?

How might these impact sustainability?

Does the project seem responsive to user needs?

- Are bug reports generally processed in a timely fashion? (note that not all bugs can be fixed quickly, but the bug reporting system should still give you a good indication of attention)

- Are contributions welcomed?

- Are there ways for participants to influence the roadmap?

- When security vulnerabilities arise, does the project handle them promptly and competently?

- Are there community participation guidelines, and are they enforced?

Will the project provide the level of support you require?

- Is the documentation around system installation and initial configuration of high quality?

- Overall, is documentation clear and updated?

- Are there commercial support providers around the product?

- If so, are they engaged in the project's development community?

- Are there active user forums? (e.g. non-commercial support)

FUTURE WORK: More in-depth evaluation templates might be useful to create in the future as this toolkit is further tested and revised. The first suggestion is a scoring and ranking template to help agencies use the points outlined in this section to more deeply assess open source products for adoption as a standalone DPG or as components in a new DPG. The second is an internal capacity assessment template aimed at helping agencies evaluate their ability to leverage the toolkit’s broader set of recommendations. These potential templates would be separate but equally important tools for decision making and planning. Such templates should start simply, but we can imagine that different weighting prioritizations might eventually develop depending on the application area, the desired social impact, or whether an agency is adopting a product generally “as is” or using it as a component. For example, an agency might place greater value on the implementation experience of a contracting vendor with a specific open source product if that product will be adopted wholesale versus as a component in a new DPG. The latter scenario might place more weight on the agency’s internal capacity to manage various open source components.

Lastly, there might be value in extending these templates to evaluate the maturity and readiness of a DPG to be implemented at the country-level, where issues such as scalability, financial sustainability, and a conducive government policy environment might be particularly important.